The Fed Should Compromise

Key Takeaways

- Fed Policy Misaligned with Market Reality: While global central banks ease and long-term yields normalize, the Fed continues to hold short-term rates artificially high, distorting the yield curve and worsening consumer credit strain.

- Steeper Yield Curve Needed for Balance: A healthier curve, with lower short rates and higher long rates, would reward duration risk, flush zombie companies, and create space for better capital allocation and labor productivity.

- U.S. Economic Strain Building: Rising delinquencies, weak consumer spending, and unaffordable housing suggest the U.S. is not far behind global peers like Germany, the UK, and China, which are already entering recession.

- Policy Compromise Can Prevent Overcorrection: A combined approach of rate cuts and balance sheet reduction could stabilize the curve, ease household burdens, and avoid reigniting inflation, offering the soft landing markets hope for.

The Fed Should Compromise

There’s a long tradition in the United States of presidents pressuring the nation’s central bank. Andrew Jackson, Dwight Eisenhower, and Herbert Hoover all publicly called for looser monetary policy to spur economic activity. Donald Trump is no different. As a real estate mogul, he understands how interest rates affect property values and determine profitability for operators.

A president’s legacy is often tied to the state of the economy, which can make or break a re-election bid. In modern times, Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush both lost second-term races amid economic downturns. In reality, a president has limited influence over the economy in their first term, as they inherit conditions shaped by their predecessor and central bank policy. The decisions they make in office often don’t show their full impact until the next president’s first term.

The Federal Reserve is neither a true federal agency nor does it hold “reserves” in the traditional sense. It is influenced by its member banks and their lobbyists. While the president nominates the Fed chair, often based on input from the most powerful bank CEOs, and the Senate confirms the choice, that confirmation typically proceeds only with the approval of the banking lobbyists who fund political campaigns. Technically, the Senate has oversight of the Fed, but beyond public posturing to appear “tough” on the billionaires who run the banks, lawmakers almost always fall in line with the wishes of their donors, who hold the real power.

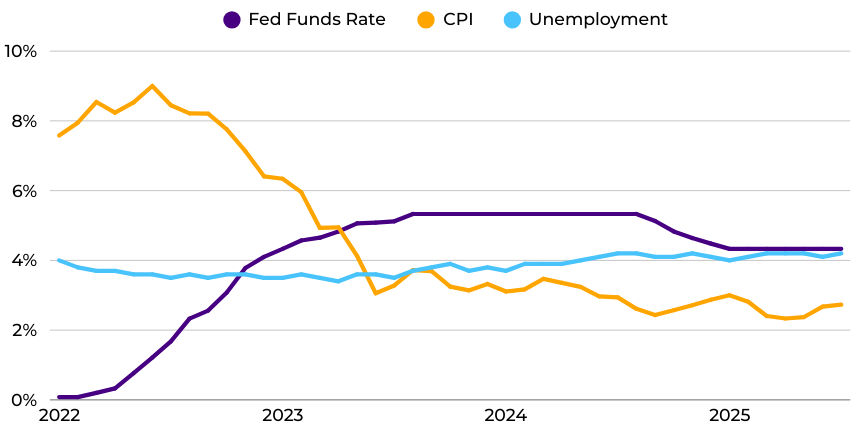

The current Fed is undeniably political. Over the past four years, we accurately predicted most of its policy moves by analyzing how they would affect electoral outcomes rather than inflation or unemployment. For example, we forecast that the Fed would cut rates in 2024 primarily to improve the Biden Administration’s chances of winning a second term, despite inflation being higher and unemployment lower than today. While the Fed insists it is independent and data-driven, the table below, showing policy decisions alongside inflation and jobs data, suggests otherwise. Even during a period of massive government spending that pushed inflation into double digits, Chair Powell dismissed concerns as “transitory” rather than tightening policy to counteract them.

With inflation now in the 2–3% range and unemployment edging higher, the Fed has paused its rate cuts. Global data points to a slowing economy, prompting other central banks to ease policy. The UK lowered rates earlier this month, the fifth cut since August last year, bringing them to their lowest level in over two years. The ECB began cutting in 2024, reducing rates eight times to the current 2.15%. China has been cutting since 2021, now holding rates at 3% while also buying assets. In contrast, the Fed has kept rates at 4.25%–4.50% since November 2024, while maintaining QT.

.png)

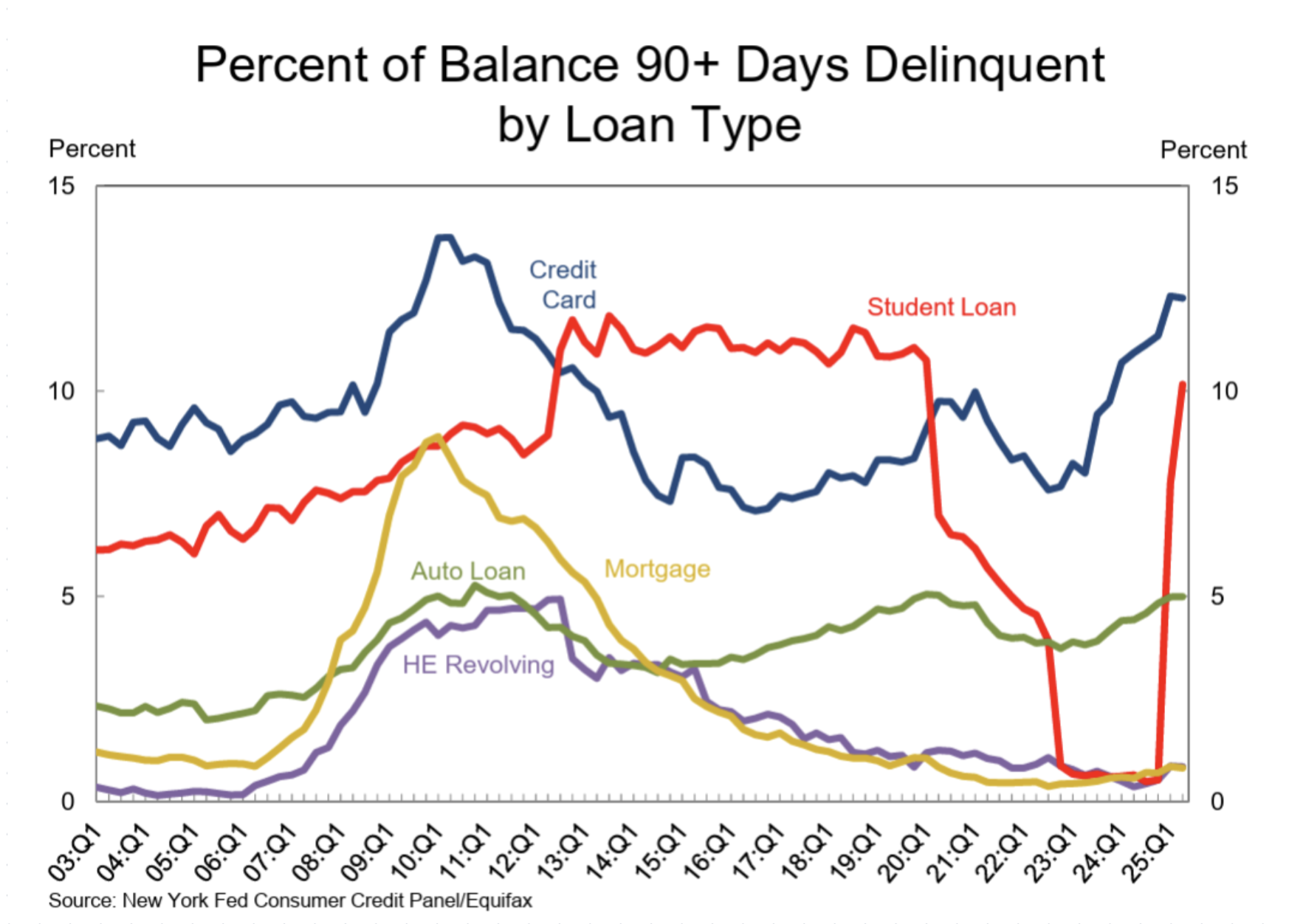

In the US, auto loan delinquencies have reached an all-time high, alongside rising student loan defaults, growing credit card balances, and increasing mortgage delinquencies. Additionally, flight bookings are down(1)(2)(3), restaurant reservations have declined(4)(5)(6), and hotel bookings have decreased(7)(8).

.png)

Yield Curve

Although the data is interesting, I see the full picture in one chart: the US Treasury yield curve. A normal yield curve rewards lenders for taking on longer-duration risk by offering higher yields than short-term debt. The yield curve has been inverted since the summer of 2022, and technically uni-inverted in late 2024, however, the short end continues to produce a higher yield than certain maturities on the long end and the belly.

.png)

Take the long end, for instance. Recently, there have been failed auctions for both the 10-year and 30-year Treasury notes. Why? In the past month, the 10-year yield fell from 4.5% to 4.25%, and the 30-year yield dropped from 5% to 4.5%. Why would a prudent bondholder buy 10-year paper at 4.25% when 3-month paper offers the same yield? The only reason would be the expectation that 10-year yields will fall significantly in the near term, generating enough capital appreciation to compensate for the longer risk. Or, the curve is simply mis-priced.

Fed Action

The Fed is keeping short-term rates artificially high. They should be lowered to restore a normal yield curve that reflects market forces. That doesn’t mean all rates should come down, I support higher long-term rates and lower short-term rates.

To be clear, I advocate for:

- Real estate prices continue to fall.

- Unemployment continues to rise.

- Zombie companies continue to fail.

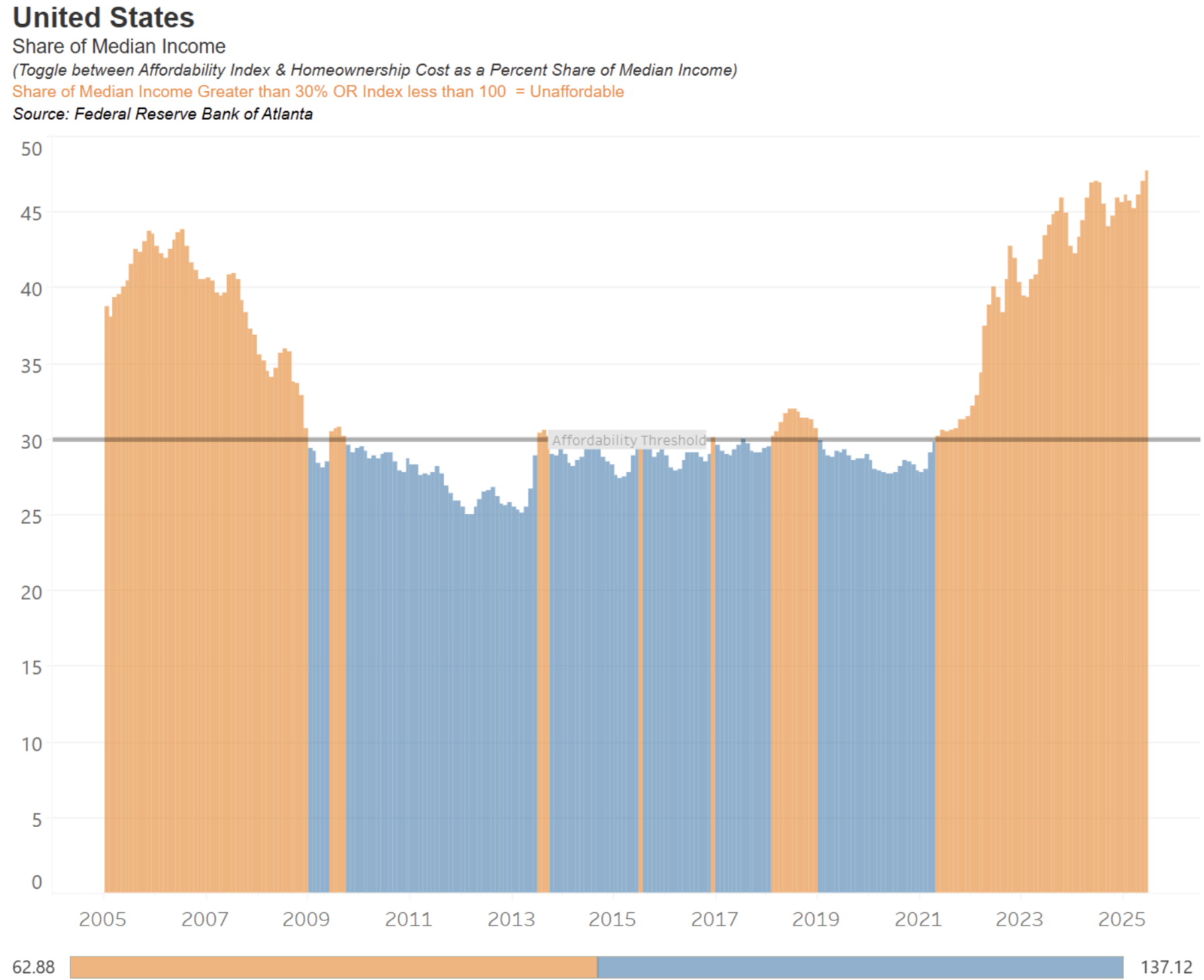

Real estate has been propped up by loose monetary policy since 2009, and again in 2020, with the effects lingering for years. Housing is now unaffordable for most consumers: home prices have doubled in the past four years while real wages have stayed flat. Because mortgage rates are tied to the 10-year Treasury, I support keeping the 10-year yield near 4.5%. Commercial properties, also overpriced, should follow, which is why the 30-year should be around 5%.

Unemployment remains too low at 4.5%; the natural rate is closer to 5%. Why? Roughly three standard deviations of the population are simply not suited for sustained employment, and much of the remaining two standard deviations will still cycle in and out of jobs. While unemployment is creeping higher, we’re not there yet, and this ties directly to the issue of zombie companies.

Zombie companies produce goods and services that exceed natural demand but survive because low interest rates let them roll over debt (“amend and extend”) indefinitely. They generate just enough profit to cover interest payments but never pay down principal. Most issue shorter-term debt tied to the 5-year Treasury, currently at 3.75%. A move to 4% would be enough to flush many of them out, which would in turn push unemployment higher.

This isn’t heartless, the high-quality workers displaced from these companies would move to more productive firms, creating better products and advancing their careers. In the long run, it’s a win-win.

Many working Americans can’t keep up with credit card payments or afford basic necessities like food. Since both credit and many commodities are priced off the short end of the yield curve, lower Fed rates would directly ease this burden by pushing short-term rates down.

How could the Fed achieve this?

The idea isn’t unprecedented, Operation Twist in 2011 flattened the yield curve by selling short-duration securities and buying long-duration ones to stimulate housing. Today, the Fed should do the opposite.

I propose lowering the Fed Funds Rate by 50 bps in September, 25 bps in October, and another 25 bps in December, totaling 100 bps. Ideally, the cuts would have started earlier (May, July, September) in three 25 bps increments, but delays now require a sharper move. To control inflation while cutting rates, the Fed should:

- Continue letting maturing debt roll off its $6.6 trillion balance sheet.

- Sell longer-dated securities to push the 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year yields toward 4%, 4.5%, and 5% respectively.

This would steepen the curve, reward duration risk again, and give the President the rate cuts he wants, without fully loosening policy and risking a new inflation wave.

Some argue that even if the Fed lowers the policy rate, long rates could rise on their own, making balance sheet sales unnecessary. Historically, the entire curve has moved lower when the Fed cuts, but last year was an exception: the Fed lowered rates despite high inflation, and the 10-year and 30-year yields rose due to perceived duration risk.

The Balance Sheet Problem

The Fed’s $6.6 trillion in securities, including Maiden Lane holdings, is unprecedented relative to GDP. Of this:

- $3.5 trillion matures in 10 years or more.

- $2.1 trillion is mortgage-backed securities (MBS) bought during the housing crisis, down from $2.3 trillion last year as maturities roll down the curve.

- $1.6 trillion is long-dated U.S. Treasuries, up from $1.5 trillion last year.

Despite “tightening,” the Fed still bought $55 billion in 10-year Treasuries over the past year, artificially holding down yields. Selling these long-dated Treasuries and MBS, if necessary, would normalize the curve faster.

At the current pace, the Fed has reduced its balance sheet by $600 billion in the past year simply by letting assets mature, but it still equals 25% of GDP. Accelerating runoff and sales could bring it down toward a more normal 5% of GDP. This would restore policy flexibility for the next recession, which may be close at hand, as Germany, the UK, China, and Japan have already seen their economies stall.

.png)